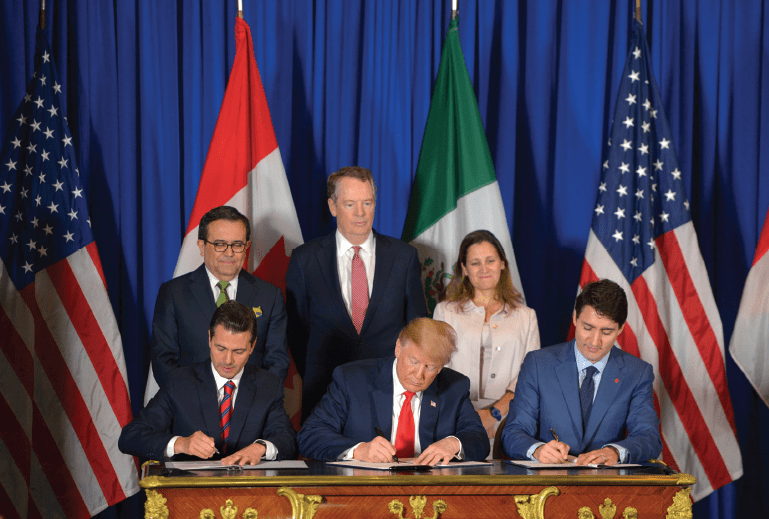

It’s been more than a year in the making, but the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) was finally signed on Nov. 30, 2018, at the G20 summit in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

While the document may now have the autographs of Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, U.S. President Donald Trump and outgoing Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto, it still must be passed by each country’s legislature. It’s expected that in the U.S., at least, a vote on USMCA will be delayed until January. Given the antagonism between Trump and the Democrats, some people believe we could be into April 2019 before any action is taken.

Trudeau, who appeared less than enthusiastic during the USMCA signing ceremony and in fact neglected to refer to it by name, took the opportunity in his post-signing speech to remind Trump that, “there’s much more work to do, in lowering trade barriers and in fostering growth that benefits everyone. And, Donald, it’s all the more reason why we need to keep working to remove the tariffs on steel and aluminum between our countries.”

Even though Canada signed an important USMCA side letter that will allow it to export up to 2.6 million passenger vehicles into the United States tariff-free, the steel and aluminum used to build those automobiles remain the casualties of an ongoing trade war between Canada and its largest trading partner.

On June 1, 2018, the U.S. imposed tariffs of 25 per cent and 10 per cent on imports of Canadian steel and aluminum, respectively. The Department of Commerce implemented the tariffs under a rarely-used American trade clause that allows the country to levy tariffs against materials that “threaten to impair the national security.” The tariffs – and the reasoning behind them – were unprecedented and seen as a major threat to the Canadian economy.

On July 1, 2018, Canada fired back with a retaliatory tariff package on up to $16.6 billion in imports of steel, aluminum and other products from the United States. The dollar-for-dollar countermeasures represented the 2017 value of Canadian exports affected by the U.S. tariffs.

According to the Canadian Steel Producers Association, more than 11 million tonnes of steel, worth over $14 billion, were traded between Canada and the U.S. in 2017. Canada buys more than 50 per cent of U.S. steel exports, making it the number one foreign destination for that product. In fact, American steel imports cover one third of Canada’s domestic market needs. Likewise, the United States is the number one market for Canadian steel, taking in roughly 90 per cent of Canada’s exports and almost 45 per cent of domestic steel production. However, steel imports from Canada only represent about six per cent of the U.S. domestic market.

The Government of Canada says the steel industry employed more than 23,000 Canadians in 2017 and contributed $4.2 billion to Canada’s gross domestic product (GDP). Meanwhile, the aluminum industry employed 10,500 people and generated $4.7 billion towards Canadian GDP.

Political motivation

Prominent steel economist Dr. Peter Warrian says the tariffs are about politics, not economics. Warrian, who is Senior Research Fellow at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs, said the Canada-U.S. steel trade is already relatively balanced.

“If you count by number of tonnes or by dollar value, basically after 20 years of the NAFTA [North American Free Trade Agreement], it’s relatively balanced,” he told Piling Canada. “Depending on how you count, there may be $6 or $7 billion of steel going each way annually. It basically evens out. The issue is on the political side. It’s the election of Trump and him choosing to make a major issue about the U.S. trade deficit. In fact, overall in Canada – forget steel for the moment – the Americans have a trade surplus with Canada. There is no deficit as Mr. Trump says.”

Warrian said the political undercurrents impacting the steel trade are what make the current situation so “difficult and frustrating.” While the national security reasons cited by the U.S. may never hold water with the World Trade Organization, it may take years for the issue to have its day in court. “But meanwhile, if you’re out there running a company, the damage can be done,” said the steel economist.

The U.S. tariffs are being felt by steel producers like ArcelorMittal Dofasco in Hamilton, Ont., which is heavily entwined with the auto industry. About 40 per cent of the factory’s flat roll steel goes to the U.S. Now, it costs American buyers 25 per cent more to buy that Hamilton steel. The moment the shipment arrives at the border, the tariff must be paid – or the truck will be denied entry. Technically, the U.S. government says the purchaser must pay the fee; however, Warrian said buyers and sellers will often split the cost of the tariffs.

Pricing pinch

The three biggest consumers of steel (in order) are the automotive, construction and energy sectors. Warrian said the deep foundation construction industry may in fact be more affected by Canada’s retaliatory tariffs, which add 25 per cent to the cost of steel items imported from the U.S.

“The piling industry may be seeing a major upward shift in prices and cost,” he said. “That’s the real impact – the steel tariffs have certainly raised the cost of steel to the end user.”

Higher steel and aluminum prices were cited by General Motors as one reason for lowered profit forecasts in 2018. It’s estimated the tariffs will cost the company $1 billion this year. In June, GM warned that possible U.S. tariffs on imported vehicles and an escalating trade war would lead to “less investment, fewer jobs and lower wages.”

Then, GM announced on Nov. 26 that it would be closing three North American plants, including the factory in Oshawa, Ont., and reducing its salaried workforce by 15 per cent in 2019. The company’s CEO, Mary Barra, said GM is moving toward electric and autonomous vehicles, and is acting now to “stay ahead of fast-changing industry and market conditions.” Tariffs were not specifically mentioned as a cause of GM’s restructuring. Warrian said tariff wars never benefit anyone, but they escalate quickly once they get started.

“Short term, people will find steel wherever they can,” he said. “But with tariffs on both sides of the border, they will have difficulty. They may look to source more steel in Canada, but they will still be looking at serious increases in steel prices.”

He added that steel prices in the U.S. have gone up by 43 per cent in the last six months. The recent low was US$429 per metric ton in May 2009, rising to US$1,006 in July 2018, and then US$864 in November 2018.

“No one has a crystal ball, but we can expect to have elevated steel prices for an extended period of time,” said Warrian. “U.S. consumers are now feeling that cost in their consumer goods. It starts to feed through inflation. It’s probable that higher prices have eased some of the direct pressure from the tariffs, but higher prices can also put your customer out of business. It’s very complicated, and it’s very complex.”

Canadian companies that buy construction steel are also feeling the pinch. To prevent the country from being flooded by cheap overseas steel that was blocked from the U.S. by Trump’s tariffs, the Canadian government imposed a further series of tariff rate quotas on Oct. 25, 2018. The new measures apply to seven classes of steel goods and shipment-specific import permits are needed in order to exempt the shipper from a 25 per cent Canadian import tax.

The system is reportedly causing havoc when it comes to importing construction-related materials such as rebar and other steel products and is resulting in delayed or deferred projects. It is becoming increasingly difficult for builders to predict the price of basic materials and therefore bid for future work with any certainty.

According to a Nov. 8 news release from the Vancouver Regional Construction Association (VRCA): “At stake are some 60,000 construction jobs across Canada according to estimates prepared for the Canadian Coalition for Construction Steel, with disproportionately higher impacts likely for British Columbia because of how and where rebar and related products must be sourced.”

VRCA said steel from the U.S. is more expensive to buy since Canada imposed tariffs on July 1, and it is too expensive to ship Canadian steel across Canada by road or rail. That only leaves sourcing steel from Pacific Rim suppliers, which is now more expensive due to safeguards.

“The combination of tariffs on U.S. steel imports and safeguards on non-U.S. steel imports is a double whammy for B.C.’s construction industry and will result in higher prices, supply restrictions and delayed or deferred projects in the B.C. marketplace,” said Fiona Famulak, VRCA president. Meanwhile, experts say the path out of the steel and aluminum trade war likely involves some sort of quota system – and of course, that will take time to negotiate.

Preparing for tomorrow

Now that Canada has negotiated the best deal it can with USMCA, it’s time to look inward, suggested Warrian.

“The barriers to inter-provincial trade within this country are a bigger problem than international tariffs,” he said. “We must have a grown-up conversation about the barriers to trade and mobility within Canada – they are economically a bigger cost issue than the American tariffs are. We have to look ourselves in the eye. The second thing we can do is look at our education and training – are we getting ready to use the latest technology?”

The topic of interprovincial trade was also on the agenda for the First Ministers’ Meeting in Montreal on Dec. 7, where Prime Minister Trudeau was expected to discuss the issue with provincial premiers from across the country.

According to a federal government press release, trade between provinces and territories accounts for just under one-fifth of Canada’s annual GDP, or $370 billion. It also accounts for almost 40 per cent of all provincial and territorial exports. Estimates suggest that removing interprovincial trade barriers could result in an economic benefit roughly comparable to the projected benefit of the Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement.

As Warrian said, economic opportunities exist if one knows where to look. “The positive part of that is we are not hostages [to tariffs]. We can influence our own destiny,” he said.